Originally published at Becker’s Hospital Review.

Trauma centers save lives

Serious injury is the leading cause of death for Americans between the ages of 1 and 44, and after cancer and the heart disease-stroke complex, injury results in the most years of life lost. Injury prevention is the most effective public health strategy available, but when serious injuries do occur, trauma centers save lives.

Even at very good hospitals, when there is not a trauma center, 20 to 40 percent of injured patients who arrive alive suffer a preventable death, simply because a team of surgeons and nurses with the necessary skill and experience is not immediately available to provide definitive care.

Gaps and threats

During the last 25 years, with leadership by groups including the American College of Surgeons and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, we have come a long way toward providing all citizens with rapid access to a trauma center. Regional trauma systems have developed to the point where, in 2012, approximately 82 percent of the U.S. population can reach a Level 1 or Level 2 trauma center within one hour by ambulance or helicopter.

But this means that approximately 45 million Americans still do not have adequate access to this level of care. Level 3 trauma centers help to fill some of this gap for rural and remote communities. However, there are not enough hospitals willing to become Level 3 centers. Many long-established trauma center hospitals, particularly in our big cities, report large operating losses for their trauma programs. To the extent that these hospitals will need to close their trauma centers just to keep their basic services operating, hard-won improvements in access to life-saving care will be reversed.

Trauma centers also save money

Trauma centers not only save lives. They also save money.

Even when insurance companies pay for the true cost of trauma center care (at what might seem at first glance to be premium rates), they still save money. This is because trauma centers — while fulfilling their primary role of saving lives — also prevent complications and disabilities. This shortens length of stay and reduces the use of costly aftercare.

In a landmark study published in 1981 in the New England Journal of Medicine, Seelig, et. al. showed that for patients with acute subdural hematoma, a delay to neurosurgery of less than two hours (compared to delays of four to six hours) resulted in a much higher survival rate. In addition, rapid surgical treatment enabled significantly more patients to achieve good functional recovery and led fewer to suffer severe disabilities. Similar findings about functional recovery were published in the Journal of Trauma by Bone, et. al., based on a two-year study related to the rapid treatment of major fractures found in centers in Baltimore, Buffalo, Camden, Nashville, Seattle and Tampa.

Commercial insurance companies often take a short-term view of cost and fail to recognize that, if they resist paying the rates necessary to sustain trauma centers, trauma centers that are needed will not be established or will be shut down. When this happens, the total cost to insurance companies will actually increase.

Strategies to secure financial self-sufficiency

So, what can an established trauma center do when it sees large operating losses? What can a hospital do when it knows it could fill a critical gap in geographic access by establishing a Level 3 trauma center but is fearful that it will lose money?

Here are five strategies:

- Separate contracting for trauma center services from routine services. View the trauma center as a vital public health service and more than just another one of the hospital’s services.

- Establish the expectation that the trauma center should be fully financially self-sufficient. This calculation should provide for all direct costs and a full and fair allocation of indirect costs. Without such an allocation, other hospital services would need to subsidize the trauma center, which would not be fair to those patients and their insurance companies. Financial self-sufficiency requires not only fully recovering total costs, but also earning a modest operating surplus — appropriate based upon the needs of the hospital for capital to keep technology and facilities meeting modern standards.

- Assure that trauma center costs are as efficient as possible. Even though public agencies control most cost elements, some trauma centers have room for improvement in cost management.

- Determine the average rates of payments from commercial insurance companies that are necessary for full financial self-sufficiency, after allowing for the reality of low, fixed payment rates from Medicare and Medicaid and patients without insurance. These rates are usually expressed as either full standard charges or a high percentage of charges. This means trauma centers with higher proportions of Medicare, Medicaid and uninsured patients will need to have higher rates of payment from commercial insurance companies.

- Educate commercial insurance companies about their pivotal role in securing the regional trauma systems in their communities. Contract with commercial insurance companies at the required rates on an equitable basis. These rates should not only result in financial self-sufficiency but also be competitive. Competitiveness can be tested by analyzing public and proprietary data on charges and proprietary data on commercial payment rates.

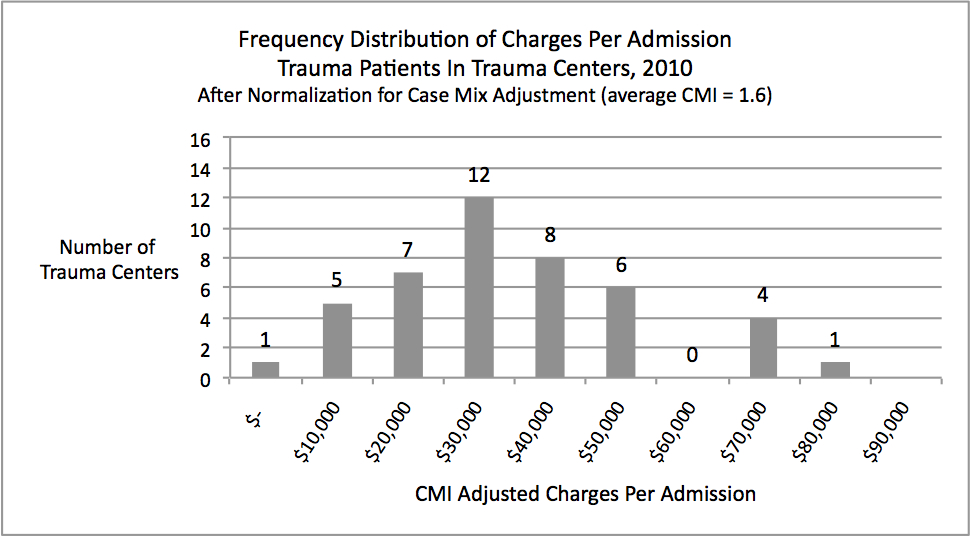

The last part of this fifth step — testing prices for competitiveness — should not be taken for granted. The chart illustrates the striking variability in charge levels, even after normalization for case mix index, among all of the 44 designated Level 1 and Level 2 trauma centers in one state for which excellent public data are available. Experience indicates that at least 25 percent of these trauma centers (those in the lower portion of the chart) have charges that are too low to achieve financial self-sufficiency and are unnecessarily low in that market range. Many of these hospitals are likely to be unaware of their relative position.

Moreover, studies of financial performance of trauma centers reveal that nearly half operate at a loss after full allocation of indirect costs. Many even operate with a negative contribution margin. Only a few operate with excessive margins and charges that are above competitive levels.

Established and proposed new trauma centers should guide their financial management by careful attention to assuring competitive prices and attaining a modest operating margin after full and fair accounting for direct and indirect costs of care. When this occurs more uniformly throughout the United States, the live saving and cost saving benefits of top quality trauma care will be available to all who need it.